Portable Peer Review: The Pros and Cons

What do iPhones, umbrellas, and peer review have in common?

Answer: They’re all portable.

You can take them with you. Even peer review. Portable peer review, at least.

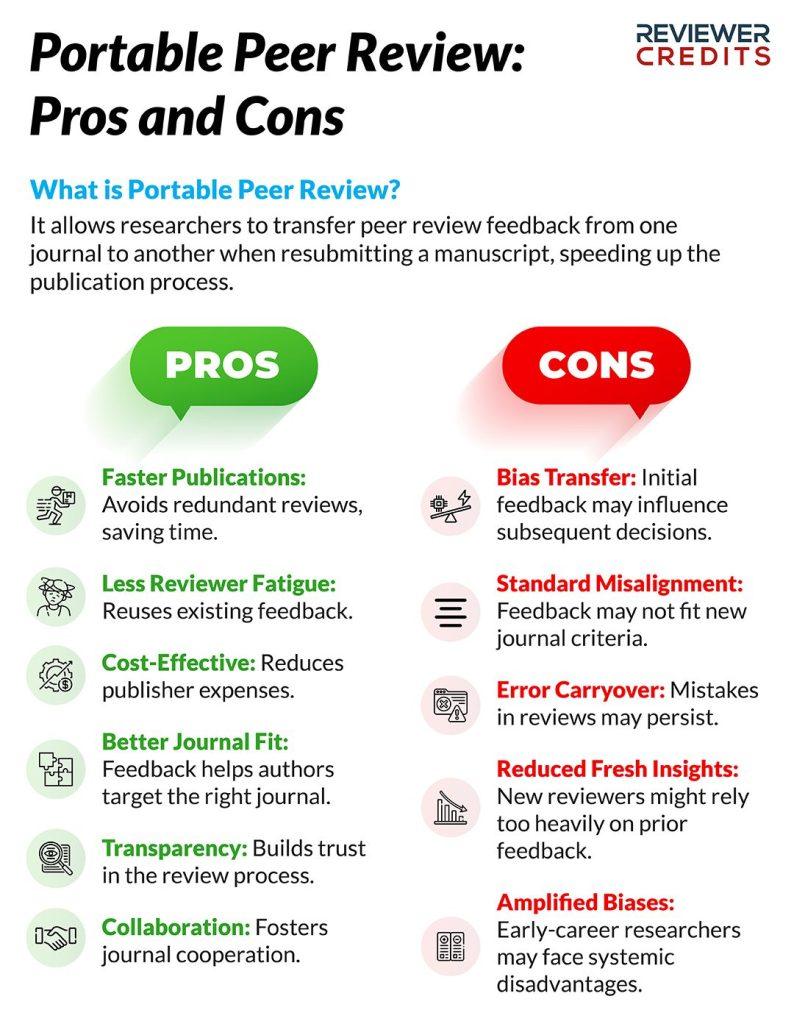

Portable peer review lets researchers transfer peer review feedback from one journal to another if their manuscript is resubmitted elsewhere after a rejection. The feedback they receive can follow their manuscript, helping speed up the publishing process. That’s less work for reviewers and editors.

This model streamlines the review process and reshapes the academic publishing landscape. But, naturally, this mode of peer review has pros and cons.

While it saves time and effort, making disseminating new research faster and more efficient, it also raises concerns about review quality and appropriateness because standards can vary between journals.

This article digs into the benefits and possible shortcomings from a journal editor’s perspective and in the interest of transparent and effective review and research.

First, what is portable peer review?

Portable peer review is a system in which peer reviews of academic or research manuscripts are transferred between different journals, publishers, or even (less commonly) institutions.

The main goals of portable peer review are:

-

-

- Reduce redundancy

- Speed up the publication process

- Improve efficiency by reusing reviews and feedback across different journals

-

In the peer review model that most journals use, after rejection, a manuscript typically has to go through a new round of peer review at the second choice venue, even if similar or identical feedback was already given. This causes delays and unnecessarily strains reviewers, who may review the same manuscript multiple times for different journals

Researchers submitting manuscripts commonly see the process as redundant and inefficient. They face long wait times between submission and publication due to multiple rounds of peer review, even after rejection and resubmission to a new journal.

Portable peer review solves these issues, as authors can submit peer review they’ve already received from one journal to another (most often within the same publisher, but they can be within the same subject area) if their manuscript is rejected or withdrawn.

A brief history of portable peer review

The idea of making peer reviews transferable between journals began to gain traction with open access publishers in the early 2000s as a potential solution to the inefficiencies discussed earlier: the same reviewers working on the same manuscript redundantly, and the accompanying time spent on this.

Groundbreaking open access publishers like BioMed Central and the Public Library of Science (PLOS) were among the first to explore mechanisms for reducing and managing redundant reviews. These publishers allowed authors to transfer reviews and decisions from one of their journals to another in their portfolio, setting the stage for broader adoption.

Later, in the 2010s, several large academic publishers and journal networks began experimenting with formal portable peer review systems. Springer Nature, for instance, introduced the Transfer Desk, which lets authors move manuscripts, along with their reviews, between journals in their ecosystem without restarting the review process and Elsevier and other major publishers began developing similar mechanisms across their journal portfolios.

Around the same time, independent services emerged to facilitate “portable” peer review across publishers. Peerage of Science (founded in 2010), for example, aimed to create a pool of peer reviews that could be used across journals.

Another key player was Rubriq (launched in 2013), a platform designed to provide portable peer reviews that authors could submit alongside their manuscripts to various journals.

More recently, platforms like Review Commons (launched in 2019 by EMBO and ASAPbio) offer peer-reviewed preprints that can be submitted to journals across publishers.

Current status of portable peer review

The growth of open science and preprint platforms has also supported the rise of portable peer review. Preprint servers (like arXiv, bioRxiv, medRxiv, and Research Square) allow for manuscripts to be openly reviewed and commented on by the community, and these reviews can be used when submitting to journals.

Some preprint servers and journals have begun collaborating to integrate reviews directly into the submission process (e.g., Research Square as part of Springer Nature)

The COVID-19 pandemic, which highlighted the need for faster scientific communication, further accelerated interest in portable peer review. Journals and preprint platforms sought to reduce bottlenecks in the review process to quickly disseminate critical research.

Organizations such as ASAPbio, a non-profit advocating for open peer review, have pushed for greater adoption of portable peer review systems in the context of transparency and reproducibility in science. This also applies to the emerging platform PREreview.

Pros of portable peer review

While there’s great promise in the portable peer review model, there are potential pitfalls. Both warrant ongoing debate. First, the pros.

Eliminates/reduces redundant peer review

In traditional peer review, if a journal rejects a manuscript, the author typically (may revise it and then) submits it to a different journal. Then, the manuscript must go through a new round of peer review from scratch. This leads to multiple, often identical, reviews of the same work. Portable peer review eliminates this by transferring the existing reviews, so a new journal can use the previous feedback instead of repeating the process.

Journals often rely on a limited pool of subject-matter experts. When a manuscript is resubmitted to different journals, the same experts might be asked to review it again, wasting their time and efforts. Portable peer review allows their initial review to be reused, preventing them from being asked to do redundant work.

Faster decision-making, less time for authors

When a manuscript is submitted to a new journal with previous reviews attached, editors at the new journal can make decisions more quickly. They can choose to accept the prior reviews, suggest revisions based on them, or add only minimal additional reviews, reducing the need to start over.

Authors save time by not having to undergo multiple rounds of peer review when submitting to different journals. Once a manuscript has been reviewed, the feedback can be reused at other journals, significantly speeding up the publication process.

Journals working together

Journals collaborating through portable peer review create a more interconnected scholarly ecosystem. This can foster better relationships between journals, publishers, and reviewers, and promote a more cooperative approach to academic publishing. A good example is the Neuroscience Peer Review Consortium, which brings together 70+ cooperating journals.

By streamlining the review process, journals and publishers can reduce the administrative costs associated with coordinating multiple rounds of peer review for the same manuscript. This can lead to a more efficient publishing industry overall.

Publishing in more-suitable journals

By reusing peer reviews, authors can target more appropriate journals for their work after an initial rejection. Journals receiving these submissions have more information from previous reviews, which can lead to better matches and higher acceptance rates.

Authors have more control over their research journey. If a manuscript is rejected, they can transfer the existing peer reviews to a new journal without starting from scratch. This reduces frustration and improves the chances of publication in a shorter time.

Transparency in peer review

Portable peer review also often encourages a more transparent process. With open reviews or the ability to see past feedback, authors and editors gain trust in the integrity and thoroughness of the peer review process.

Cons of portable peer review

With all pros, there must come cons. Upon further review, portable peer review does have its shortcomings. Bias is foremost.

Bias transfer

The potential for bias transfer in portable peer review can be problematic. When a manuscript is initially reviewed, the reviews’ feedback and tone may carry certain intentional or unintentional biases. These biases may relate to the reviewers’ specific research views, personal stances on the manuscript’s topic, or even implicit biases toward the author’s institution, region, or career stage.

As this review is transferred to subsequent journals, each journal’s editor and new reviewers may be subtly influenced by the existing review tone or comments, which can limit fresh, independent assessments.

Editors at the second journal may feel pressure to follow the lead of the initial reviewers, particularly if the original reviewers are well-known figures in the field or if the initial reviews are very positive or very critical.

This deference to previous opinions might discourage editors from taking an entirely fresh approach, potentially leading to decisions that reflect others’ biases rather than the new journal’s independent evaluation.

When an editor or reviewer sees prior negative or positive reviews, they may unconsciously look for flaws or strengths that align with the previous assessment. This confirmation bias can lead to a more one-sided evaluation of the manuscript’s merits or weaknesses, reducing objectivity in the review process.

If the original review contained subtle or unintentional biases, these may be amplified rather than mitigated in subsequent rounds.

Reviewers in the new journal might feel constrained by the need to agree with prior feedback, leading them to suppress or moderate their own opinions, especially if they disagree with the initial assessment. And this might dilute the diversity of perspectives that a fresh peer review normally provides, stifling new insights or critical feedback that could benefit the manuscript and its author(s).

Alignment of review standards

Each journal has unique criteria for significance, rigor, and fit with its scope. Portable reviews, however, are generally conducted with more general standards and may not align with the specific standards of a particular journal.

Editors may feel pressure to align their journal’s standards with those implicitly endorsed by the original review, potentially impacting the journal’s unique identity and quality control over time.

For early-career researchers or authors from underrepresented institutions, bias in the initial review may reflect broader systemic biases present in academia. If these biases are transferred to subsequent journals, it may further disadvantage these authors.

This effect could reinforce disparities in publishing success between well-established researchers and those newer to the field or from lesser-known institutions.

Errors can be carried over, rather than corrected

In traditional peer review, each submission to a new journal allows for a complete re-evaluation, which can sometimes help correct mistakes or unfair critiques in previous reviews. But, when reviews are portable, any errors or oversights in the original review may follow the manuscript through multiple submission rounds, potentially perpetuating incorrect critiques or overvaluing certain points without fresh analysis.

Editors and new reviewers must remain mindful of prior feedback’s influence and strive to approach each review as independently as possible.

Lots of promise, if the bias can be dealt with

Portable peer review offers a flexible, streamlined approach to academic publishing by allowing researchers to transfer peer reviews between journals. This reduces redundant reviewing, speeds up the publication process, and enables authors to reach broader audiences more efficiently.

It also fosters a collaborative environment in which reviewers’ insights are preserved and valued across platforms, ultimately improving the quality and accessibility of scientific research. As a result, portable peer review benefits authors, reviewers, and journals alike, promoting a more open and efficient research ecosystem.

Portable peer review or initial peer review, we’ve got you covered

Reviewer Credits lets you access a database of thousands of best-fit reviewers who are ready to do an initial peer review, secondary, or any type of peer review. For busy journal editors, this is a massive time relief.

And if you’re a peer reviewer, here’s your chance to get recognized for your work and build your own skills while earning Credits you can use to improve your own submissions.

Journal editors and publishers, get started here.

Peer reviewers, see your benefits here.