What is Peer Review? A Brief but Spectacular Guide

Peer review is the process by which experts in a specific academic/scientific field assess and critique the quality, validity, and relevance of scholarly authors’ research and academic publications, such as manuscripts and books. Through this process, peer reviewers help academic publishers decide if the work is suitable for publication, needs revision, or is unfit for publication. Other researchers trust published peer-reviewed research as material they can cite and apply in their own work.

Peer review is the cornerstone of academic publishing, though it wasn’t always that way. Peer review is steeped in the tradition of cooperating for the sake of sound, reproducible science. Its roots date back centuries, and the modern form is not so different from the original. Rather, the main differences are in technology, publication types, and adjusting to the booming amount of submissions.

This post explores peer review’s history, objectives, types, challenges, and other aspects of the pivotal role it plays in advancing knowledge.

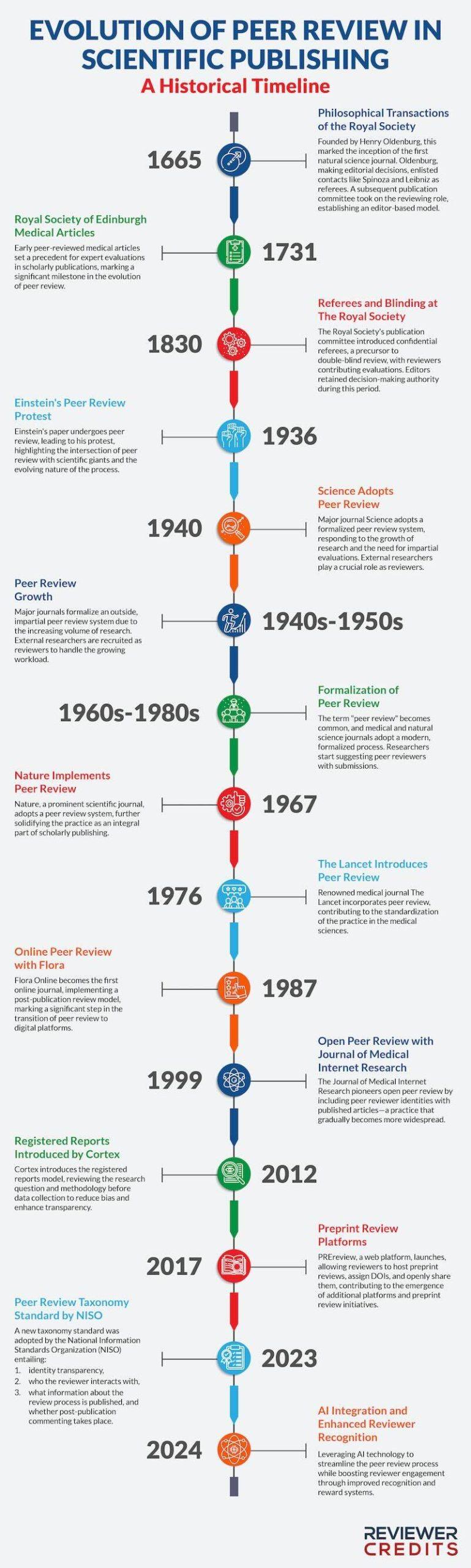

A rapid history of peer review

The Royal Society of Edinburgh’s Medical Essays and Observations, published in 1731, is usually cited as the earliest example of peer review; thus, the peer review process we know today has evolved gradually over the last three centuries.

Throughout the 18th and early 19th centuries, scientific communication occurred through letters, monographs, essays, public presentations, and pamphlets. Economic pressures and the labor required, however, kept peer review uncommon. External refereeing was also uncommon in these formats.

The modern concept of peer review started taking shape in the mid-19th century, with journals like the Philosophical Magazine introducing more formal evaluation processes. External experts’ views, not just the editor’s, on the quality and validity of submitted content started to be sought. By the early 20th century, the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA), Science, and other journals began more systematically adopting peer review.

The post-World War II era saw a large increase in scientific output and specialization. With this rise came greater competition for journal space. That demand and the need to manage the growing volume and complexity of submissions sped up the adoption of formal peer review processes with leading journals, including Science and Nature, adopting full peer review in the 1940s and 1960s, respectively.

Digital revolution

The digital revolution from around the 1990s transformed scientific publishing from paper-based to electronic, making disseminating information much easier and faster. This technological shift also enabled the widespread use of peer review and new models such as open and transferable peer review.

More recently, journal publishers like BMC, Frontiers, and Springer Nature (Scientific Reports and Nature Communications) have embraced open peer review, where reviewer identities and comments are published alongside articles, promoting transparency and accountability (usually on an opt-in basis). This mode of peer review has been shown to remove bias and lead to better, more constructive comments on research.

Peer review continues to evolve, with ongoing debates about its effectiveness, potential biases, and alternative models that will ensure research quality and integrity.

Einstein’s unspectacular experience with peer review

Albert Einstein’s experience with peer review in 1936 is a notable example of early resistance to the process. Einstein submitted “Do Gravitational Waves Exist?” to Physical Review, received critical comments suggesting key improvements, and wasn’t pleased with what happened, so he withdrew the manuscript. In his curt refusal, he said he hadn’t authorized the journal to send the manuscript for review.

He then published it somewhere else. Interestingly, the reviewer was likely Howard Percy Robertson, whose advice Einstein would later incorporate into the final version after informal discussions. Ultimately, despite Einstein’s resistance, peer review worked.

Who can be a peer reviewer?

Being a peer reviewer is considered both a privilege and a chore. Performing this typically voluntary and unpaid role is thought of as a researcher’s implicit duty in upholding good science. (If you want to be rewarded for your peer review, have a look at Reviewer Credits here.)

Peer reviewers should be experts or scholars with substantial knowledge in a certain subject area. They can be senior academics like professors and seasoned researchers with extensive publication records. However, early-career researchers (ECRs) and postdoctoral fellows can also serve as reviewers, especially if they have specialized expertise and a publication record.

Graduate students nearing the completion of their doctoral studies may be invited to review under the guidance of a senior mentor. They can also make themselves known to journals and use services like Reviewer Credits to list themselves as available for review.

Professionals working in industry with relevant experience can also contribute valuable insights. The key qualification is a deep understanding of the topic and the ability to provide objective, constructive evaluation. Today’s journal editors also should seek a diverse (in terms of experience, gender, and geographic location) panel of reviewers to help ensure a thorough and balanced assessment of the research.

The purpose of peer review

Peer review fundamentally exists to ensure quality, integrity, and relevance in published scholarly work. A common misconception among researchers is that peer review exists to help them improve their work, but in actual fact, this is a fortunate by-product of the process. The following are peer review’s main objectives.

Ensuring quality research

Peer review is a quality control mechanism for journals and other academic publications. Experts in the same or an adjacent field evaluate the manuscript to ensure it meets scholarly research standards. This process helps to:

- Verify the research methods’ accuracy and validity

- Assess the soundness of conclusions

- Identify potential errors or oversights in the research

Improving research

Improving/enhancing the quality of research before publication is a top goal of peer review, if not the top goal. Reviewers provide constructive feedback that, ideally, helps authors:

- Refine their arguments

- Clarify ambiguous points

- Address potential weaknesses in their methodology

- Improve the overall presentation of their work

Filtering and selecting what will be published

Peer review helps journal editors make informed decisions about which manuscripts to publish. The review process can:

- Determine if research is relevant to the journal’s (or another publication’s) scope

- Assess the work’s potential impact on the field and interest to others

- Pick out flaws in the scientific methodology, presentation, and even the language quality

- Ensure that published research meets the journal’s quality standards

Credibility and trust

Published peer-reviewed articles have far greater credibility within the academic community than non-peer-reviewed articles (such as those on preprint servers). The review process:

- In an implicit endorsement, builds trust in the research findings

- Raises the reputation of authors and their institutions

- Provides a benchmark for reliable academic information

Advancing the academic field

Peer review contributes to the progress of academic disciplines by:

- Encouraging critical thinking and debate

- Identifying gaps in current knowledge

- Suggesting new research directions

Professional development

The peer review process benefits not only authors but also reviewers and editors:

- Reviewers gain insight into cutting-edge research in their field

- Reviewers gain access to the editorial process and even a relationship with an editor

- Editors develop a deeper understanding of publishing standards

- Authors receive insightful feedback to improve their work and research skills

Evidence suggests that peer review, despite its limitations, remains a crucial component of academic publishing. One study (Severin and Chataway, 2020) found that peer review serves multiple purposes, including assessing contributions to the field, verifying quality, improving manuscripts, evaluating suitability for specific journals, and aiding editorial decision-making.

While typically involving at least two reviewers, the exact process can vary between journals. Regardless of the specific approach, the overarching goal remains consistent: to uphold the standards of scholarly research and contribute to advancing knowledge in the field.

Types of peer review

At least two dozen types of peer review exist to suit different fields, publications, and needs. These types are evolving, but the four most common models are as follows.

Single-blind review

Also known as single-anonymized review, the single-blind model is where the reviewer knows the authors’ identities, but the authors don’t know the reviewers. Single-blind encourages more honest and critical reviews, as the reviewers have no fear of retaliation. However, it increases the chances of intellectual theft and may encourage harsh and excessively mean-spirited reviews. The European Society of Radiology switched from double-blind (see below) to single-blind for its journals in 2023, basically to give its reviewers a more complete picture of the authors while acknowledging the difficulties of maintaining complete anonymity.

Also known as single-anonymized review, the single-blind model is where the reviewer knows the authors’ identities, but the authors don’t know the reviewers. Single-blind encourages more honest and critical reviews, as the reviewers have no fear of retaliation. However, it increases the chances of intellectual theft and may encourage harsh and excessively mean-spirited reviews. The European Society of Radiology switched from double-blind (see below) to single-blind for its journals in 2023, basically to give its reviewers a more complete picture of the authors while acknowledging the difficulties of maintaining complete anonymity.

Double-blind review

In double-blind review, the authors don’t know the reviewers and the reviewers don’t know the authors. This dual anonymity can help prevent bias based on, for example, the author’s nationality, gender, and previous publications. Ideally, the manuscript is judged solely on its content. Authors can’t expect advantages based on their reputation, while reviewers focus on quality, originality, and significance. Some Nature journals, such as Nature Neuroscience, use double-blind review, and this is generally preferred by authors from some global regions, as seen with China and India.

Triple-blind review

Triple-blind peer review anonymizes authors, reviewers, and editors from one another; i.e., no one knows who anyone is. This presents a logistical challenge, but it goes a step further from double-blind review by completely removing bias. This model is especially effective in high-stakes research fields or in areas where qualitative assessment is central. In these areas where anonymity is vital to ensure research evaluation is based only on quality and merit. It can also prevent the editor’s subconscious bias from familiarity with authors or institutions. The Journal of Applied Philosophy uses “triple-masked” review, another term for triple-blind review.

Open (or transparent) review

In an open review, there is complete transparency, and all individuals know the other party’s identity. This may allow the authors to receive fairer and more civil reviewer feedback. However, this also makes the critique of the manuscript susceptible to bias due to the reputation of the author or the reviewer or personal differences. The BMJ moved to open review in 1999 for transparent reporting and assessment of medical research.

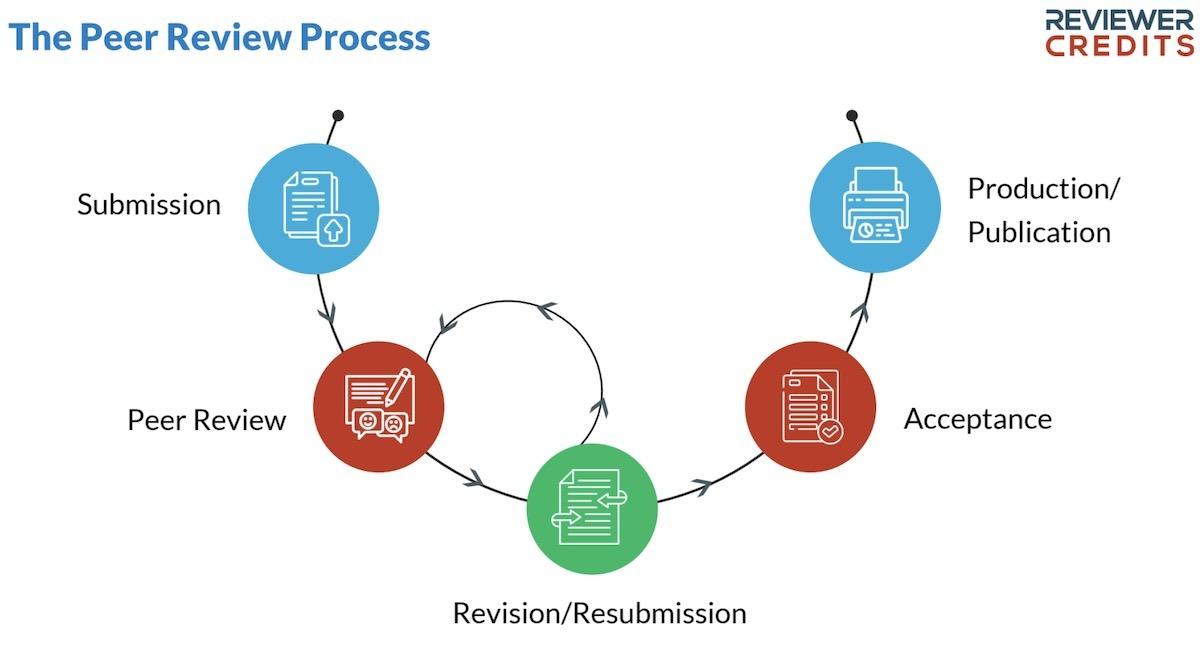

The peer review process

The peer review process is the integral part of the great publication process. Peer reviewers serve as a jury, but not the final judge (that’s the editor). There are three key parties in the peer review process:

- The manuscript’s author(s) – Submit their research

- The journal editor – Evaluate the research for publication

- The peer reviewers – Expertly assess the research contents

There are many exceptions and styles (such as preprints, conference papers, and books), but a scholarly journal’s typical peer review process goes like this…

Step 1: Manuscript submission

The corresponding author submits the manuscript to their publication (e.g., journal) of choice on behalf of all co-authors having received their permission to do so.

This submission should include all the elements the journal requires, including the full author and affiliation list, the abstract, main text, figures, tables, supplementary materials, declarations (e.g., conflicts of interest), and references. ORCiD IDs are often also required.

The manuscript should follow the journal’s guidelines on formatting, word count, citation style, and ethical considerations.

Step 2: Initial editorial assessment (desk review or editorial triage)

After manuscript submission, the journal editor does an initial screening called a desk review or triage. During this stage, the editor evaluates:

- Relevance to the journal’s scope: Does the manuscript align with the journal’s focus and objectives? (hint for authors: be sure to read the journal’s Aims and Scope page)

- Originality and contribution: Does the work offer new insights or significant advancements in the field? If not, does it offer another valuable contribution? Essentially, the editor is looking for an answer to the question, “So what?”

- Compliance with submission guidelines: Has the manuscript followed all the journal’s formatting and structural requirements?

- Writing quality: Is the text clear and free of grammatical errors and is the English (or other target language) mature and readable?

- Ethical standards: Have the authors addressed all necessary ethical approvals and disclosures, such as meeting human or animal research standards, having IRB approval, or conflicts of interest?

- Will the work be interesting to the journal’s readership? (this is an increasingly high bar as the journal’s Impact Factor increases)

If the manuscript doesn’t meet these criteria, the editor may reject it without sending it for peer review. That’s called a “desk rejection.” It’s not the end of the line, however, as the authors may have the chance to fix up the initial shortcomings.

In sum, step 2 helps filter out papers unsuitable for the journal before involving peer reviewers.

Step 3: Selecting peer reviewers

If the manuscript passes initial assessment, the editor normally selects two or three peer reviewers who are experts in the research area (or more, depending on the degree of acceptance from reviewers) Reviewers are chosen on factors such as their expertise, lack of conflicts of interest, and ability to meet the review deadline. Finding reviewers is often a time-consuming and tiring task for editors (see our guide for journal editors), but they have many tools to help them with this process.

The editor sends the manuscript to these reviewers, often with specific evaluation guidelines, and assigns a deadline for completion.

Step 4: Peer review evaluation

Peer reviewers critically assess the manuscript for:

- Scientific validity: Are the research methods sound and appropriate?

- Data analysis: Are the data interpreted correctly, and are the statistical analyses suitable?

- Clarity of results: Are the findings presented clearly and do the data support them?

- Strength of conclusions: Do the conclusions logically follow from the data?

- Literature integration: Have the authors adequately cited research and made the case for their work among this literature?

- Ethical compliance: Did the research follow relevant ethical guidelines?

- Overall level of interest and significance to the field.

Reviewers provide detailed feedback, highlighting strengths, identifying weaknesses, and suggesting improvements. They may recommend acceptance, revisions, or rejection.

Step 5: Editorial decision

The editor makes one of the following decisions based on the reviewer’s reports and the editor’s own assessment:

- Accept without changes: This indicates the manuscript is ready for publication as is, which is an extremely rare outcome.

- Minor revisions required: Small changes are needed and the manuscript may not need further review after revision (usually just by the editor).

- Major revisions required: Significant changes are needed. The revised manuscript may need to go through another round of peer review and will usually be returned (or at least offered) to the original set of peer reviewers.

- Reject: The manuscript is not suitable for publication in the journal. However, the editor may recommend a partner journal, such as a more general open-source or lower-impact journal. This step is called “transfer” or “cascade,” and often, peer review reports from the initial submission can be retained and even considered again at the next journal. Journal cascades are usually within individual publishers but can also be subject-area-specific, such as in neuroscience.

The editor informs the authors of the decision, including the reviewers’ comments and suggestions.

If it was a rejection, it’s back to Step 1 for the authors. If minor or major revisions are needed, on to the next step.

Step 6: Revision and resubmission

If the editor requests revisions, the authors should:

- Review the comments.

- Revise the manuscript carefully: Make the necessary changes to the text, figures, and tables.

- Highlight changes: Some journals ask authors to highlight revisions in the manuscript for easy reference.

- Write a point-by-point response explaining what steps were taken to address each comment. This should be diplomatic and mature, no matter how curt or imprecise the peer reviewers’ comments may have been. This response might help convince the editor that the work should be published.

Timely and thorough responses increase the chances of acceptance. The authors should provide a clear and respectful explanation if they disagree with a comment and/or didn’t make the suggested revision.

Step 7: Secondary review (if applicable)

For major revisions, the editor may send the revised manuscript back to the original reviewers. The reviewers will then assess whether the authors adequately addressed their concerns. This step can be repeated until all three parties are satisfied.

Step 8: Final decision and publication

After all revisions are complete, the editor makes a final decision:

- Acceptance: The manuscript is accepted for publication.

- Rejection: The manuscript may still be rejected if the revisions don’t meet the reviewers’ and editor’s expectations. And again, another journal may be suggested.

Upon acceptance, the manuscript moves into the production phase, which normally includes typesetting, and eventually, publication. It may also include copy editing/proofreading.

Become a peer reviewer (or find peer reviewers)

Now you know all about peer review, take the next step – YOUR step. Get involved.

Peer review remains the cornerstone of academic publishing. It maintains quality and integrity in scholarly work, ensuring the publication of science that advances humanity. As an author or editor, you proudly take on this responsibility, and we offer resources to support you.

- Do you want to deepen your understanding of peer review even further? Continue your journey here.

- Do you want to become a peer reviewer? See how here.

- Are you seeking peer reviewers for your journal? We have your solution here.

Join thousands of reviewers and a community of publishing experts, and help advance knowledge in your field, the scientific community, and worldwide.

Learn more from an expert. Watch this Reviewer Credits webinar to keep growing your peer review knowledge…